Summary of 17 June Elections (2nd Round)

There appears to have been a positive step change in Colombian politics, with more voters than ever before engaging in the electoral process.

– Louise Winstanley, ABColombia Programme and Advocacy Manager

In the second round of presidential elections on 17 June 2018, Ivan Duque (Centro Democratico – Democratic Centre Party) was elected as Colombia’s President with a majority of the votes: 53.98% compared to Gustavo Petro’s (Colombia Humana) 41.81%. There was a higher electoral turnout than in the second round of the 2014 presidential election, which saw 47.89% of the electorate voting, whereas 53.04% cast their vote in 2018; this is the highest turnout since 1998.[1] This number of people voting in Colombia, combined with less violence at the polls suggests there has been a key step change, and people consider that their vote matters.

In the past I have generally heard, especially in rural areas, that people had sold their vote for “food or drink” because they believed that their vote would make no difference – so why not get something for it. This time when visiting remote areas in Colombia, I heard the comment, ‘The land-owner is furious because some people in this area voted for Petro.’ This shows how people have started to engage in the election process and voted for the candidate they themselves wanted to see in Government.

– Louise Winstanley, ABColombia Programme and Advocacy Manager

The general voting pattern in Colombia also provides evidence that people considered their vote mattered in these elections, with a wide range of votes for candidates with differencing political positions. In the first round of the presidential elections, the majority of votes were distributed between Duque, Petro and Sergio Fajardo; with Fajardo on 23% and Petro on 25%.

Despite the result of the presidential election, this was a historic moment for the left with Petro winning over 8 million votes (8,034,189). In addition to being the first openly left wing candidate to arrive at the second round of the presidential elections[2], Petro is also the first left-wing candidate in the history of Colombia to obtain that number of votes in the second round. Interestingly, ex-president Santos obtained just over 7.8 million votes when he was elected in 2014.

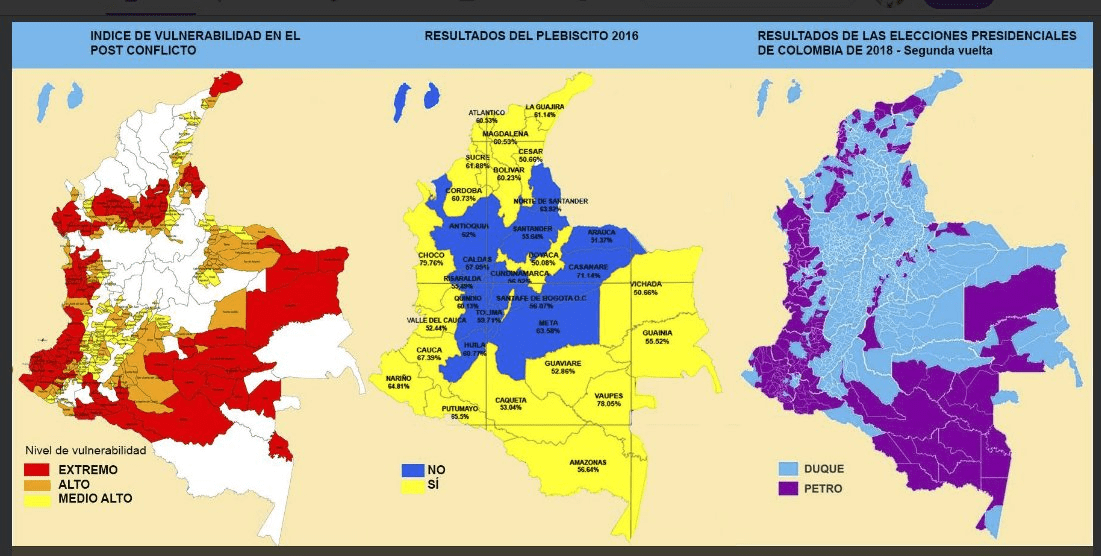

The pattern of voting to an extent reflected the 2016 referendum, with Petro winning the majority of votes in departments and municipalities around the periphery of Colombia (the Pacific Coast, Sucre, Atlántico, Putumayo) as well as the capital city of Bogotá. In some regions, where the impact of the armed conflict has been acute, such as Catatumbo, Nariño and Chocó, Petro obtained more than 80% of the votes.[3] Duque won a majority in 23 of the 32 Colombian departments, including Antioquia, and in the central regions of Colombia. Another historic moment saw the appointment of the first female vice-president in the history of Colombia.[4]

Election: a positive step forward following the peace process with the FARC

As Colombia is engaged in a Peace Process with the largest of the guerrilla groups, this level of engagement with the electoral system is a positive signal that a growing number of people think change can be brought about through politics rather than through internal conflict. According to the Defence Ministry, not a single violent incident occurred during the elections.[5]

Despite the left/right polarisation in respect of the two final candidates, these elections were a move away from the traditional two-party Conservative and Liberal Party race and towards the left and the Greens.

Duque will now need to seriously consider this level of engagement in politics, and the over 8 million people who supported the policies put forward by the “Colombia Humana” (Human Colombia) campaign of Petro, including on issues such as development. Many voting for Petro are concerned that an economic development policy formulated around making Colombia more attractive to multinational corporations with a reduction in taxes and a major increase in the extractives industry will exacerbate the existing high levels of inequality[6] and increase the tensions in mineral-rich regions of the country. These policies are concerning not least because economic analyst Guillermo Rudas discovered that when government income from taxes and royalties were balanced against the rebates given, the coal industry in Colombia in 2007 and 2009 were effectively being paid to take away the coal.[7]

The extractives industry is already generating waves of social protest and conflict, as land belonging to Indigenous people and afro-Colombian communities has been concessioned to multinational companies without adequate prior consultation and consent, as required by Colombian and international law. Clarity over land ownership and completion of the land restitution process is currently progressing very slowly and there are millions of hectares still needing to be restored to victims. It is crucial that this happens before encouraging investment by multinational and national companies in projects related to land and agro-industries.

The objections to the Peace Accord from Duque and his most prominent supporter, ex-president Álvaro Uribe Vélez, are also concerning at this stage of the peace process. Senators from the Centro Democratico recently signed a proposal with support from far-right representatives of the Conservative Party, Radical Change and a good part of the Unidad Nacional for the remainder of the legislation related a procedural code for the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) to be removed from the legislative agenda. This is a serious threat to the peace process and to the rights of the civilian population as the implementation of the JEP is a crucial element in addressing the rights of the victims of the conflict.

Peace Accord

The international community have financially and politically provided strong backing for the implementation of the Peace Accord. Early on in his election campaign, Duque was strongly against the implementation the Peace Accord. However, as his campaign progressed, and it became clear that this was not a policy that would attract voters, he did change his discourse on this, being far more selective about what he would not implement. However, in his speech following the first round of the elections he never once mentioned “peace” or the “peace process.”

Nevertheless, he is unlikely to want to cause a major breach with the international community by refusing to implement large sections of the Peace Accord. It is most likely that he would simply under-fund and under-resource the institutions that are responsible for implementation, making the process at best weak, if not impossible.

The interference from the USA in insisting that fumigation of coca crops should be resumed, may now find agreement with the incoming administration of Duque (7 August 2018). Aerial fumigation has been a negative practice which proved to be completely ineffective despite millions of dollars poured into fumigation campaigns under Plan Colombia. According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the social and economic policies together with crop substitution outlined in the Peace Accord have proven to be the more effective way of achieving a reduction in coca cultivation.

Policies agreed in the first chapter of the Peace Accord on rural reform are also crucial for victims. Supporting a mixed economy with just and sustainable policies for small scale farmers, ethnic communities’ and local economies will help to build peace, especially in the rural areas. However, it is unclear how much support Duque will provide for the legislation and sufficient resources for implementation of the first chapter of the Peace Accord on rural reform.

Furthermore, if the Peace Accord is “modified”, this will affect the possibility of negotiations with the second largest guerrilla group, the ELN. Duque’s attitude to date has been against any real negotiated peace deal with the ELN and it is very likely that he will impose impossible conditions on the ELN negotiations, these could eventually lead to a break down in the Talks. This would be a real setback in the Colombian peace process and put communities at increased risk. The peace talks with the ELN are being supported by ABColombia partner, the Diócesis of Quibdó.

Fundamental for a just and sustainable peace in Colombia is the implementation of the commitments made to victims who have borne the brunt of the brutal conflict in Colombia.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes:

[1] La Silla Vacia, Con Iván Duque, llega el uribismo 2.0 al poder (17 June 2018)

[2] Portafolio, Gustavo Petro y los desafíos de la izquierda en segunda vuelta (30 May 2018)

[3] La Silla Vacia, Con Iván Duque, llega el uribismo 2.0 al poder (17 June 2018)

[4] El Tiempo, La carrera de Marta Lucia Ramirez, la primera mujer vicepresidenta (18 June 2018)

[5] Colombia Reports, Colombia’s vote was historically peaceful after aggressive campaign (17 June 2018)

[6] Colombia is one of the most unequal countries in the world. With a Gini Index of 0.53, Colombia is the second-most unequal country in Latin America. See: https://colombiareports.com/colombia-latin-americas-2nd-unequal-country-honduras/

[7] See ABColombia Report, Giving it away: the consequences of an unsustainable mining policy in Colombia, November 2012. It may well have been an issue over many more years than just 2007 and 2009 but these were the only complete figures that Rudas had been given access to by the National Planning Department of the Republic of Colombia.

Further Reading

- ABColombia, Results of the Colombian Congressional Elections 2018

- ABColombia, FARC becomes a Political Party