Emblematic Case: Buenaventura

Buenaventura: Population and Geography

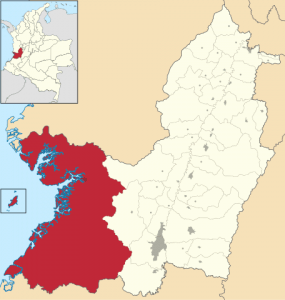

Buenaventura is a municipality in the department of Valle del Cauca on the Pacific Coast of Colombia. The municipal area covers the port city of Buenaventura and surrounding rural areas. The Pacific Coast in general, and Buenaventura in particular, are rich in natural resources and potential for mining.[1] At the same time, Buenaventura is one of the most dangerous cities in South America.

Buenaventura is the city with the highest percentage of Afro-Colombian population in Colombia. 98% of its approximately 400,000 inhabitants are Afro-Colombians, 1% are Indigenous and 1% Mestizos.[2] Displaced rural people, many of whom seek shelter in Buenaventura, are particularly vulnerable due to racial discrimination, violence and precarious living conditions.

Buenaventura: a major port for international trade

The strategic position of Buenaventura makes it an important city for Colombia’s economy and the Pacific region in particular. The highway between Buenaventura and Cali is one of the only two roads that connect the Pacific Coast with larger cities in the interior. The port was expanded with a major injection of foreign investment to become the largest deep-water commercial port in South America and the busiest in Colombia. It is now among the 10 most important ports in Latin America. It manages approximately 75% of Colombia’s internationally traded goods, generating large profits for corporations and contributing significantly to Colombia’s tax revenues.[3] The economic significance of the port of Buenaventura is constantly increasing: in 2016, 17.6 million tons of cargo were transported through the port; in 2017, already more than 20 million tons. Sugar and coffee are the main export goods shipped.

While the State has focused on economic growth through the expansion of the port and enhancing opportunities for businesses and tourism, there are numerous reports of human rights violations as a direct consequence of business investment in Buenaventura. Afro-Colombian communities report that many of the large infrastructure projects in the city were implemented without consultation, in violation of national and international human rights law.[4] As the port is expanding, poor communities are displaced violently to make space for economic development projects. For instance, according to the Inter-Church Commission for Peace, the construction of a freshwater port in the Buenaventura region contributed to the displacement of indigenous people from the lower parts of the Calima and San Juan rivers.[5]

Due to its strategic position and its advantageous road and river transport routes, Buenaventura is also a trading corridor for illegal goods. In recent years, trafficking and micro-trafficking of drugs and arms have increasingly contributed to violence and displacements among local communities.

Displaced families in Buenaventura find themselves with poor humanitarian assistance due to inefficient – or lacking – infrastructure and technical support. There have been numerous cases of children and adults with fevers, diarrhoea, nausea, and people have poor access to the necessary medical care. There is not enough food, little or no access to clean water, and not enough resources for a decent livelihood. Several young children have died of malnutrition and diseases that could have been prevented if they had had access to medical facilities. Read the ABColombia emblematic case study of the Wounaan People in Buenaventura.

High levels of poverty and lack of services

Despite its significance for international trade and tax revenue, Buenaventura is one of Colombia’s least developed cities. Buenaventura lags behind in terms of poverty-eradication, health, education and basic services. According to UNDP statistics, 80.6% of its approximately 400,000 inhabitants live in conditions of poverty, and 43.5% of the population are affected by homelessness.[6] Supplies of electricity, water, sanitation and medical services are unreliable.[7] 45% of the local population have no access to drinking water and those who do, often only have access for 6 hours per day.[8] In 2015, the city’s only public hospital was closed, leaving the population without a hospital capable of delivering anything more than the most basic primary medical care.[9]

In spite of being Colombia’s most important port city, unemployment rates in Buenaventura are very high (68%).[10] This is exacerbated by the fact that the companies involved in the large-scale development projects often recruit better skilled workers from elsewhere. Investment in training and employment opportunities for the local population are therefore essential to tackle unemployment and ensure sustainable and inclusive development.[11]

Buenaventura: A highly militarised zone

Buenaventura has seen a lot of political violence for decades. In the 1990ies, the military engaged in operations against the leftist guerrilla group FARC-EP and supporters of the insurgency in Buenaventura. From the beginning of the 2000s, paramilitary operations also started to increase in the urban centres of the port, as well as in rural areas including around the Calima and Naya rivers.

In 2014, the Colombia Caravana of Lawyers found that the military had not made real efforts to assume control in the areas most affected by the violence, and raised concerns about links between the Security Forces and neo-paramilitary structures: “[d]espite the significant increase in the presence of the armed forces in the city, this has not deterred violence and has led to questions on the independence of the military and other local State institutions within the context of widespread violence from paramilitary successor groups.”[12]

Crime and presence of illegal armed groups

Buenaventura, located on the Pacific coast of Colombia, is a territory under constant dispute by illegal armed groups, and at present forced displacement is occurring with greater frequency in the urban zone, where most of the population is Afro-Colombian. [13]

The coastal area where the port of Buenaventura is located is a strategic spot for the cocaine trade and illegal arms importation. Despite being a highly militarised town, the neo-paramilitary groups (referred to as “Criminal Gangs”-BACRIM by the Colombian Government) have a strong presence. Neo-paramilitary structures control large parts of the urban area, and local businesses are forced to pay extortion money.

Neo-paramilitary groups, which control the arms and drug trafficking, threaten, attack and kill social leaders and members of civil society organisations, impose rules and restrict free movement. Forced disappearances and child exploitation and recruitment by paramilitary groups are among the most reported crimes in Buenaventura.[14]

The recruitment and illicit use of boys, girls and adolescents is a frequent practice. The children are used as “bell-ringers” (lookouts who warn if any people enter or exit the area), as “messengers” (responsible for taking messages between the members of the illegal armed groups), to transport drugs and weapons, to provide sexual favours, to exercise prostitution and, in some cases, these children become victims of sexual violence.[15]

Between January 2010 and December 2013, more than 150 disappearances were reported, twice as many as in any other Colombian municipality. In 2014, Buenaventura hit the headlines for its “Chop Houses”. The post-demobilised paramilitary groups took people to these “Houses” at night and dismembered them alive. According to official figures (from both the Colombian Attorney General’s Office and the Ministry of the Interior published in 2015), Buenaventura saw 26 massacres, 160,000 persons forcibly displaced and more than 6,000 people killed between 1995 and 2015, in a struggle for territorial, economic and social control.

There also numerous reports of torture and sexual violence. The UN has stated that sexual violence against women and girls is used as a strategy to secure territorial control in Buenaventura, to intimidate women human rights defenders and spread terror among the civilian population.[16]

Afro-Colombian Communities: Apart from the general terror caused by the violence in Buenaventura, one critical element leading to urban displacement is the lack of formal recognition of the land rights of the local Afro-Colombian population.

Afro-Colombian communities have lived in Buenaventura for generations. Nevertheless, to date they have no recognised entitlement to the property on which they live. While Law 70 of 1991 recognises the collective ancestral land rights of rural Afro-Colombian communities, it does not recognise the collective lands of Afro-Colombian communities in urban zones, increasing the risk of displacement and exploitation these communities are exposed to.

Humanitarian Spaces

The concept of Humanitarian Spaces to create a civilian safe zone for displaced communities based on International Humanitarian Law was previously known in rural areas in Colombia. In 2014, ABColombia partner, the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace (CIJP), together with the communities, set up the first humanitarian space in an urban area: the Puente Nayero Humanitarian Space in the La Playita neighbourhood in Buenaventura.

In light of the high levels of violence in Buenaventura and serious security risks due to the presence of illegal armed groups in the city, CIJP helped the residents of the Humanitarian Space obtain precautionary measures from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.[17] Due to these measures, the Humanitarian Space must now be guarded by police officers 24 hours a day.

However, gaps in the security of the Humanitarian Space have been reported on multiple occasions, either due to the absence of police officers or collusion between police and neo-paramilitary groups. Death threats against inhabitants and community leaders of Puente Nayero also continue. In 2015, two children from the Puente Nayero community were killed. In 2018, four community leaders of the Puente Nayero community were forcibly disappeared by armed actors.

The CIJP accompanies and advises over 300 families who live in the Humanitarian Space on issues of protection, security, legal representation and provides information on human rights violations.

The 2017 Civic Strike

In May 2017, an alliance of community and grassroots organisations in Buenaventura organised an indefinite civic strike to protest against the State’s historic neglect of the Afro-descendant population. Community roadblocks around the city paralysed key routes for trade and commerce and local businesses remained closed. Indigenous and Afro-descendent communities in rural areas around Buenaventura also set up roadblocks on the highway, which is the main link between the port and the interior of the country.

The protesters eight core demands were related to the provision of basic services to allow communities to live with dignity: quality healthcare and a hospital, access to education, drinking water and dignified employment opportunities. They also protested against the environmental destruction in the area and asked for justice for victims of violence.

Human rights violations were reported as the anti-riot police (ESMAD) tried to repress the civic strike violently. Protesters and social movements received threats from neo-paramilitary groups.

The Civic Strike was eventually lifted after agreements were signed with the Colombian government. However, little has changed for the inhabitants of Buenaventura since then, and the leaders of the civic strike continue to be stigmatised and threatened.

British and Irish Parliamentarians visit Buenaventura

Watch the videos of the parliamentary delegation to hear further statements by the parliamentarians.

End Notes:

[1] Cf. Buenaventura, Colombia: Brutal Realities (Norwegian Refugee Council, 2014), p. 5.

[2] Buenaventura: El despojo para la competitividad (Comision Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz/ Mundubat, 2015) p. 7.

[3] Patrick Kane and Sebastian Ordoñez, Civic Strike paralyses Colombia’s principal pacific port (Red Pepper, 28 May 2017)

[4] Buenaventura: Displacement for a competitive economy (PBI Colombia, 29 July 2016)

[5] Father Alberto Franco from ABColombia partner the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace in an interview in the Guardian.

[6] Como romper las trampas de pobreza en Buenaventura? (PNUD Colombia, 2007)

[7] The Lawless City (Colombian Caravana of Lawyers, 2014), p. 4.

[8] The Lawless City (Colombian Caravana of Lawyers, 2014), p. 5.

[9] Patrick Kane and Sebastian Ordoñez, Civic Strike paralyses Colombia’s principal pacific port (Red Pepper, 28 May 2017)

[10] Patrick Kane and Sebastian Ordoñez, Civic Strike paralyses Colombia’s principal pacific port (Red Pepper, 28 May 2017)

[11] The Lawless City (Colombian Caravana of Lawyers, 2014), p. 5.

[12] The Lawless City (Colombian Caravana of Lawyers, 2014), p. 2.

[13] Buenaventura, Colombia: Brutal Realities (Norwegian Refugee Council, 2014), p. 6.

[14] Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados.

[15] Buenaventura, Colombia: Brutal Realities (Norwegian Refugee Council, 2014), p. 7.

[16] Sadism, Death and Abuse: Women and War in Buenaventura (Insight Crime, 16 May 2014)

[17] IACHR: Resolución 25/2014, September 2014