In recent months the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) has started to get into full swing. We have seen interesting developments including meetings between the JEP and Indigenous Authorities to reach a consensus on how the JEP and the Indigenous Justice System will work together on Transitional Justice.

The Peace Accord in establishing the principles for the JEP made two innovative decisions that have set a precedence for future Peace Processes in the global arena.

- One that has been discussed and widely published: a gender perspective and no amnesties for conflict related sexual violence.

- The other which has had less of an international profile, is the “Ethnic Focus”.

The Peace Agreement recognises Indigenous Rights in relation to the Transitional Justice System and respects the Indigenous Justice System.

The Ethnic Focus

The ethnic focus is one of the guiding principles for the implementation of the Peace Agreement. In particular, the Peace Agreement, in its ethnic chapter, establishes that the JEP must incorporate ethnic and cultural perspectives and respect the right to participation and prior consultation with indigenous peoples where appropriate. In addition, it noted that the JEP should create mechanisms for articulation and coordination with the Special Indigenous Jurisdiction.

A recent Newsletter by the Colombian Commission of Jurists they outline how this should work in practice.

Following the Peace Agreement, the rules to be implemented by the JEP include measures and mechanisms aimed at guaranteeing an ethnic focus. Equally these must comply with existing laws governing Indigenous rights.

The JEP should apply the ethnic focus to all its actions and implement mechanisms of interjurisdictional coordination and dialogue.

The ethnic focus is a guiding principle for the JEP, so it must be applied in all its actions, procedures and decisions (art. 1, paragraph c, Law 1922 of 2018). Thus, the JEP should identify the discrete impact of the armed conflict on ethnic peoples, their fundamental and collective rights (art 18, Law 1957 of 2019). In the same way, the Recognition Chamber (Sala de Reconocimiento), in presenting resolutions of its conclusions and defining the most serious cases or the most representative actions committed against indigenous peoples in the context of the armed conflict, should apply criteria that allow it to account for both the differentiated impact on indigenous peoples, as well as, their relationship with the risk of physical and cultural extermination (art. 79, paragraph m, Law 1957 of 2019).

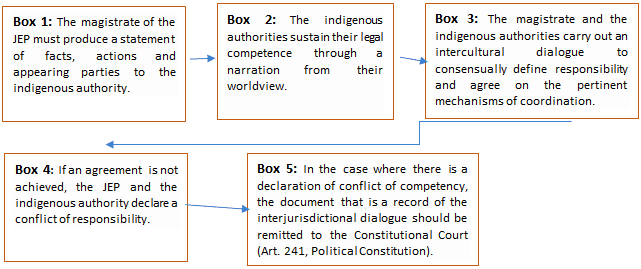

Judicial integration is an interpretative criterion for the JEP. This means that the JEP should respect the judicial functions of traditional indigenous authorities in their territorial area, as set out in the existing rules, provided that they do not conflict with the legal framework implemented by the JEP (art. 3, Law 1957 of 2019). The JEP will have a prevalence only in matters within its competence, but the State must consult with indigenous peoples through the mechanisms of articulation and coordination with the Special Indigenous Jurisdiction (art. 35, Law 1957 of 2019). In the event of a conflict of jurisdiction (arts. 98 and 99 of the JEP Internal Regulations), the JEP and the Indigenous Authorities will develop an interjurisdictional dialogue in order to resolve it in an agreed manner. This dialogue has the following steps:

Figure 1. The Stages of the Interjurisdictional Dialogue between the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) and the Special Indigenous Jurisdiction in order to resolve conflicts of responsibility.

Indigenous communities, as collective subjects, can be considered to be victims and to acquire the quality of special participants in the proceedings before the JEP, for individual or collective suffering of harm. (Protocol 001 of 2019 from the Ethnic Commission).

The ethnic authorities can be recognised as special participants in the JEP, whenever the crime has affected one or more members of its community (art. 4, Law 1922 of 2018). On being recognised as special participants, they have the right to participate in the proceedings before the JEP and act in representation of the collective ethnic subject in order to safeguard their interests, to accompany the victims and the appearing parties that they integrate, and defend their legal code. (Order 079 from 12th November 2019, Recognition Chamber).

The members of the Indigenous Peoples have the right to use their official language in all proceedings before the JEP in order to assure their full participation. For this, the JEP should guarantee access to translators and interpreters that have been previously accredited by the indigenous authorities before the JEP (art. 12, Law 1957 of 2019; art. 95, Internal Regulation of the JEP).

In the proceedings before the Recognition Chamber, the JEP can consider the restorative practices of the Indigenous Justice System, in order to promote a dialogical construction of the truth and to search for harmonisation, healing and the development of agreements (art. 27, Law 1922 of 2018).

The JEP must implement mechanisms for articulation and coordination with the Special Indigenous Jurisdiction (art. 35, Law 1957 of 2019). These mechanisms are established in the Internal Regulation of the JEP (article 96) and are as follows:

Figure 2. Mechanisms for articulation and coordination with the Special Indigenous Jurisdiction

| Intercultural and interjurisdictional communication. The bodies of the JEP have a duty to promote intercultural and interjurisdictional communication with the ethnic authorities, especially in order to reach agreements about carrying out actions in collective territories. | Notification to the ethnic authority. When the bodies of the JEP are made aware of cases involving indigenous peoples, they must notify both the person and their ethnic authority. They must use effective mechanisms that address the geographical reality and the cultural affiliation, ensuring access to advice and guidance. |

| Withdrawal of the ethnic authority’s jurisdiction. When the JEP notifies an Indigenous authority that it is, or was, involved in a past or present case, they must state whether they relinquish jurisdiction over it. The JEP must grant them reasonable and appropriate time to make this statement. | Accompaniment to the ethnic authority. In the case that the appearing party or the victim request the presence of the corresponding ethnic authority, the JEP must guarantee this. |

| Centres for indigenous harmonisation and equivalent Institutions. The bodies of the JEP can impose sanctions to be implemented in the centres for indigenous harmonisation, once the ethnic authorities have given their consent. The JEP must offer the necessary support to guarantee the conditions of the sanction agreement and supervision over it by the indigenous authorities. | Cultural harmonisation. When the bodies of the JEP are made aware of cases that involve appearing parties who belong to indigenous populations, they must request the presence of an Indigenous authority that understands the conditions of the concepts of harmonisation, admission and permanency in the ethnic territory established in their Justice System. In the cases in which it falls to the JEP to impose sanctions on the appearing party, and where these sanctions should be carried out in Indigenous territory, the JEP must obtain the Indigenous authority’s consent. |

| Handling of evidence in ethnic territories. The JEP will arrange with the Indigenous authorities the conditions and types of support needed for the collection of, or handling of, evidence in ethnic territories. | Reintegration. The ethnic communities can apply harmonising processes to members of their communities that have complied with the imposed sanction of the JEP outside of their ethnic territory. |

(Source CCJ from: Internal Regulation of the JEP)

Ultimately, the JEP has the obligation to apply the ethnic focus to all its proceedings and must therefore implement the necessary mechanisms.

To see the complete article in its original Spanish Click here and the complete article in English, an unofficial translation by ABColombia in collaboration with Volunteer Student Translators from Bristol University: Lucy Courtnall, Ami Houlbrook, Lottie Sinclair, by clicking on the PDF button at the top of this page.