Disappearance is one of the most horrendous crimes against humanity. Families live in hope, despite the odds that their loved one is still alive. Many also continue living in dangerous situations, refusing to move away from their homes for fear that their loved ones may one day return and not know where to find them.

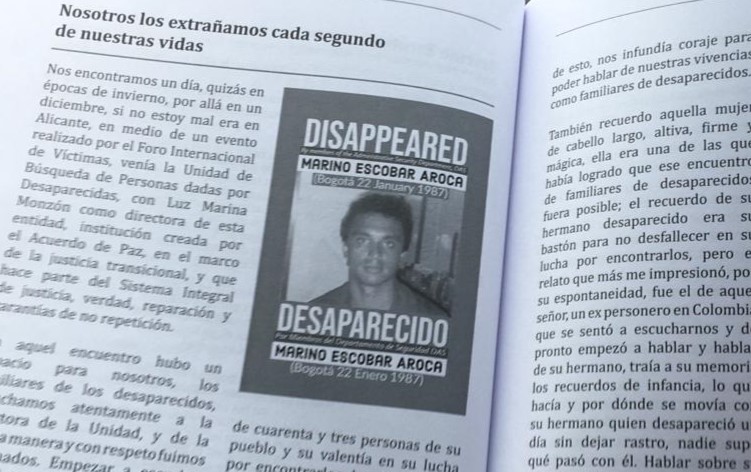

On 22 January 1987, Marino Escobar Aroca was arrested and forcibly disappeared by the notorious Colombian intelligence service, the DAS. His wife Elizabeth Santander, thirty-seven years later, continues to search for him, never giving up hope that he may return and pursing the state for answers – even using the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, with her lawyer from the Colectivo de Jose Alvear Restrepo (CAJAR). Despite being forced to leave Colombia with her young daughter in 1990, Elizabeth has worked tirelessly to search for her husband and raise awareness for the disappeared as part of the Familiares Europa Abya Yala de Personas Desaparecidas en Colombia.

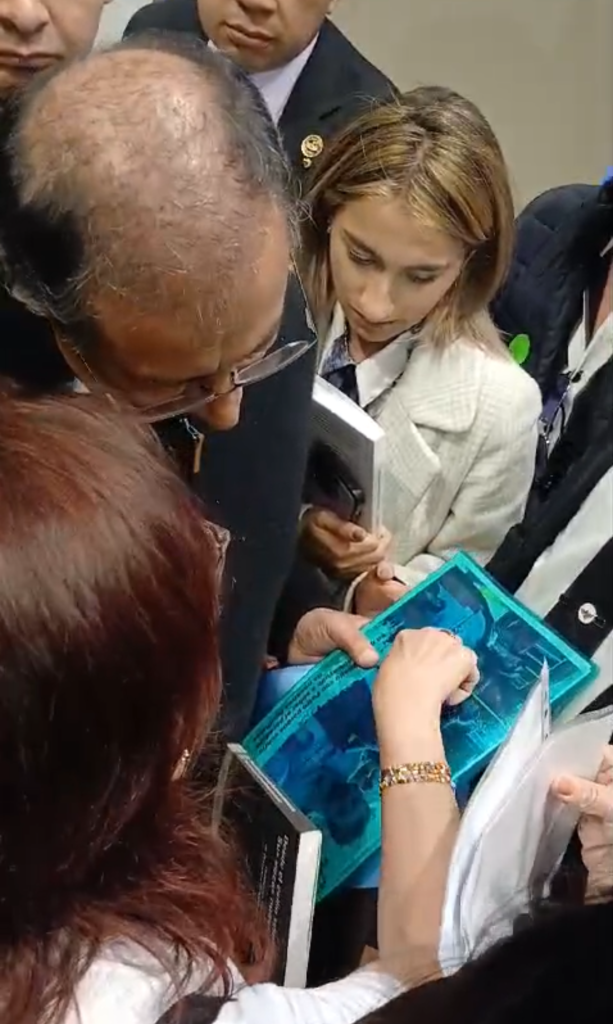

On 14 June 2024, the same day as Marino’s birthday, the Swedish Defence University hosted the forum “Transformando vidas, Seguridad y Paz Total en Colombia” in Stockholm. President Petro was present at this event as part of his official visit to Sweden this month. Elizabeth, along with other members of the Colombian diaspora living in exile, was also at the event. She personally gave the Colombian President a letter explaining her husband Marino’s case, as well as a book documenting various cases of loved ones who have been disappeared by the Colombian State, written to raise the profile of the search for the disappeared in Colombia.[i]

Elizabeth and President Petro

During the most intense years of the Colombian armed conflict, there were over 110,000 enforced disappearances throughout the country. This crime remains an ongoing issue in Colombia – despite the 2016 Peace Accord, the International Committee of the Red Cross has registered 571 new cases of missing people between 2016 and 2020. Further, as of March 2023, 89,702 people were still reported missing. The issue of enforced disappearance also persists because 99% of cases remain in impunity, and families refuse to stop looking for their loved ones.

Recognising the importance of this issue, the 2016 Peace Accord agreed to establish the Search Unit for the Disappeared (Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas Dadas por Desaparecidos – UBPD) as part of Colombia’s Transitional Justice Mechanisms. This Unit officially began operating in 2018, and has a 20-year mandate to:

- Implement plans for people reported missing in the event that they are found alive

- Coordinate recovery, identification and dignified delivery of bodies

- Design and implement National and Regional Search Plans

- Communicate the development of National and Regional Search Plans to families of victims

- Meet the requirements of the Truth Commission and submit reports regarding the Unit’s work.

The UBPD has made significant progress since its inception. Speaking at the Arria Formula Meeting on preventing and responding to persons going missing across the globe, UPBD director Luz Janeth Forero Martínez detailed the following statistics (since 2018):

- 1569 bodies recovered

- 286 bodies given a dignified return to their families

- 9058 hiding places located

- 3200 perpetrators contributing to the search

- 30 people found alive.

This month – June 2024 – alone, the Unit has recovered 16 bodies in Apartado (Antioquia), thought to be to citizens of Córdoba, Chocó and Antioquia who were disappeared between 2007 and 2016. A further 38 bodies have been recovered in San Juan del Cesar (La Guajira), also thought to be victims of enforced disappearances during the armed conflict. Óscar Alexánder Morales Tejada, whose disappearance in 2007 was investigated as part of Macrocaso 03 (the national case on murders and enforced disappearances), was finally given a dignified burial. After 16 years, Óscar’s body was identified and returned to his family who had never stopped looking for him.

The UBPD has an unprecedented task. At the UNSC, Luz Janeth Forero Martínez highlighted the challenges that the UBPD faces including the difficulty in accessing certain hiding places, especially in the jungles or regions like Chocó and Valle de Cauca, where victims’ bodies were often dismembered and thrown into rivers; searching for the disappeared in the midst of eight active conflicts in Colombia; and the low investigative, technical, logistical and financial capacity of the Unit. Cooperation between the UBPD and the UN is therefore essential if progress is to continue. For this reason, Colombia recognised the competency of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances to receive and examine complaints in 2022. The Committee plans to visit Colombia in November 2024.

There are new and concerning modalities of disappearances. For example, there has been an increase in the trafficking and disappearance of young, particularly black, girls in Cartagena. In 2011, Karina Cabaracas Peñata disappeared at 19 years old. Her boyfriend’s body was found on a beach, but Karina has not been seen since the day she disappeared. In 2021, 16-year-old Alexandrith Sarmiento Arroyo disappeared. According to local organisations in Cartagena, between July and November 2022, three girls aged 9, 10 and 11 were disappeared and raped –they were eventually rescued.

The issue of enforced disappearance remains prevalent in Colombia. Despite this, real courage and determination has been shown by the families of the disappeared, who have received death threats and some have even been forced to leave their homes and the country. Faced with this constant adversity, they have never stopped looking for their loved ones.

Today we want to recognise the work and achievements of Elizabeth and thousands of others like her – the mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, sisters and brothers who work tirelessly to reveal the truth, and lawyers like those of CAJAR who support so many in what is one of the most painful searches.

We hope that victims of this crime will one day be given dignified returns to their families

Listen to Elizabeth’s poem for her husband Marino here.

#LaBúsquedaRepara

[i] Read Elizabeth’s story in Chapter 4, pp38-48.